Queen Victoria School has a long and proud history which has helped to shape the forward-thinking approach of the School today.

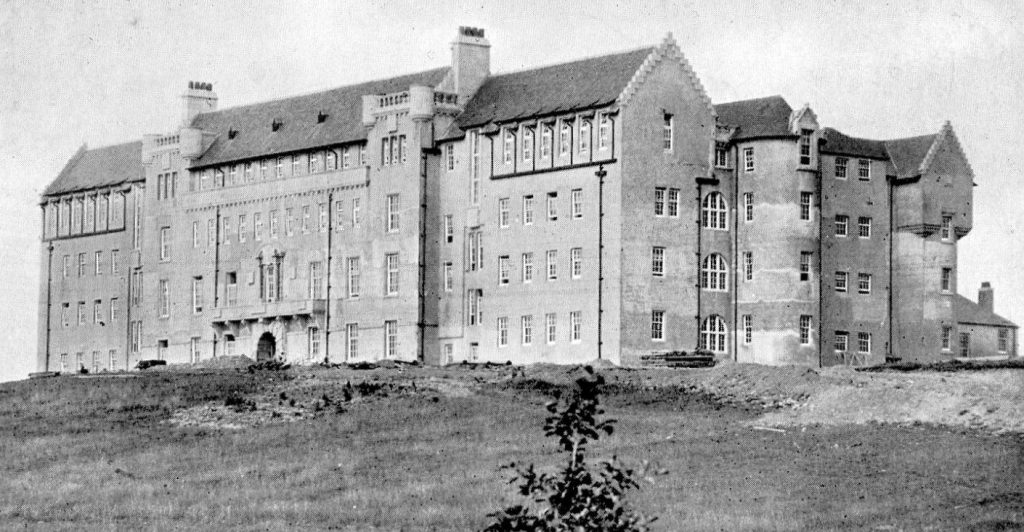

Built through subscriptions from serving personnel and other interested parties, Queen Victoria School was created in memory of those who had died in the South African wars of the late 19th Century. At that time for boys only, it was opened on September 28th, 1908 by King Edward VII; at this time he also laid the foundation stone for the School Chapel. It is Scotland’s memorial to Queen Victoria.

The original plans and purpose for the school were to provide support and education for those who were left fatherless as a result of the Boer Wars. The idea for the School was proposed to Queen Victoria after similar provisions were being provided in England and Ireland. She gave her support, and, although the school was completed and opened after her death, the school subsequently was named in her honour.

The initial concept was to build the School in, or close to, Edinburgh or Glasgow, but, in the absence of agreement which of the two would be the better home for the school, it was decided that Dunblane, virtually equidistant between the two cities, would be a good compromise. At the time of its construction, Dunblane locals named the somewhat austere building “the Jam Factory”.

Money to provide for the building was raised by soldiers giving up a day’s pay, and by support from local authorities and businesses across Scotland.

Various buildings have been added over the years:

- In 1910, the Swimming Bath was the gift of Mr Edmund Pullar.

- In the year 1913 the Hospital and Gymnasium were added.

- The Play Hall, Library and Science Room were added during the year 1914.

- The Macmillan Sports Hall in 1958 to mark 50 years of the School.

Other changes have included the admission of girls in 1996 and the move to a staff comprised almost entirely of civilians.

The central aim and purpose of the School remain unchanged, however. As one speaker put it, in 1966:

“Together with the disciplinary regime and ethos of the School, the curriculum produce(s) confident, self-sufficient, hard-working and mannerly individuals, well-suited to a range of occupations as well as to the Armed Forces… (developing) the abilities to think for oneself, get on with others and serve the community.”

Words of the early 1980s also remain true today:

“The Armed Forces face tasks today which in some ways are more difficult than those which previous generations knew, and some of this is bound to rub off on service children. If, by providing a stable education and a solid background, we can bring help where it is needed, the School continues to fulfil its purpose.”

The Opening of the School

The opening of the school was a great day. King Edward VII had travelled from Balmoral to Dunblane by train, the station was decorated with flags and red and blue bunting, a large crowd had assembled, many from various parts of Scotland and England. Amongst the crowd were Lords, Ladies, Generals, and notables from the aristocratic families of Scotland, and also I think, five holders of the Victoria Cross. The Provost of Dunblane, the Town Clerk, Magistrates and members of the Town Council were in attendance.

The Guard of Honour was provided by 2nd Bn King’s Own Scottish Borderers, with the regimental band, in front of the station and had the honour of being inspected by HM The King, before entering his carriage for the journey to the School; the carriage was escorted by members of the Scottish Horse.

The route to the School was lined by detachments of the Scottish Regiments right round to the North Gate. On arrival at the School, a further Guard of Honour from 2nd Bn Seaforth Highlanders was inspected by HM The King. After speeches, the King was given the key to open the building, after a short inspection he signed the Visitor’s Book.

At the end of the School, leading to where the Chapel was to be built, was a covered canopy through which the King walked to lay the Foundation Stone of the chapel. The King gave the stone 3 sharp taps with a gavel, then declared the stone to be well and truly laid, amid loud applause from those watching the ceremony. The short walk from the School to the chapel was afterwards known as King Edward’s Walk. After a further short speech he then left in his carriage to continue his journey back to Balmoral.

(An extract from an article written by George Dowling (No. 269) who was at the School from 1912-1917.)